The Ambling Ecosystem

May 15, 2023

Crawling slowly across the canopy, consuming foliage, and evading predators with camouflage, sloths are one of Earth’s most unique organisms. This uniqueness doesn’t stop at their slow pace, the slowest on Earth, with even slower metabolism, and muscles designed like no other creature on Earth. In fact, every sloth is an ecosystem of its own.

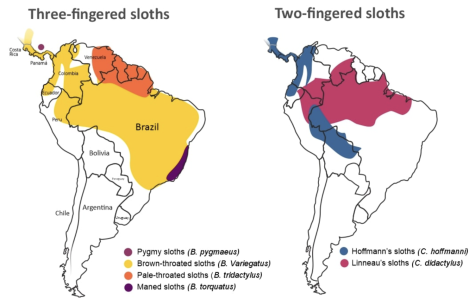

First off, what does it mean to be an ecosystem? As defined by Oxford, an ecosystem is a biological community of interacting organisms and their physical environment. So, how can a small mammal be an ecosystem in itself? To understand this, let’s take a look at the larger ecosystem that sloths reside in. As seen below, sloths live in Central and South America, where they climb among the treetops. In this ecosystem, high in humidity and chock-full of plant life, some plants take advantage of the sloth’s slow-moving nature.

The habitat range of all sloth species.

In the first place, sloth fur is very unique. As mammals, they have two layers of hair, a softer undercoat for thermoregulation, and a longer, stiffer overcoat that, unlike any other mammal, grows from the stomach towards the back, reaching its peak, known as the drip tip, along the spine. This pattern allows water to better run off of the fur, which for most mammals means from the back, down, but for the sloth, living most of its life upside down in a tropical rainforest, this means that water needs to be able to run off of its stomach. Yet, its fur also has other unique adaptations. The image below, on the left, shows the micro-cracks in sloth fur. These microcracks become home to algae, giving the slow-moving mammals their green or brown color. This alga aids in camouflage, but not just visually. Sloths produce no body odor, as the bodily secretions that would typically be consumed by bacteria, producing scent, are consumed by the algae. Thus, the sloths simply smell like their algal armor. This is a mutualistic relationship. These relationships exist among many species, but never in such a format as sloths and their algae ecosystems. In addition, it has been found that many of the algal species found on sloths have anti-bacterial traits, and some algae have been observed to carry chemicals that help prevent cancer and common diseases in sloths.

Left: Micro-cracks in sloth guard hair provide room for algal growth. Right: A moth living in a sloth’s fur ecosystem.

Yet, this mobile ecosystem isn’t home to just algae, but several invertebrate species, including five species of moths. As seen above, all five of these moth species are only found in the fur and excrement of sloths, meaning they are endemic to the ecosystem that is the sloth. Scientists are unsure what role the moths play in the maintenance of the sloth’s ecosystem, beyond maintaining algal growth, and the sloths don’t eat them, yet, the sloths are unbothered by the moths and have been for thousands upon thousands of years.

Another intriguing aspect of these moths is how they reproduce. Sloths only climb down their trees to poop once every five days, during which they can excrete nearly ⅓ of their body weight! In doing so, the moths that live in their fur lay eggs in the feces. In those five days the eggs hatch and the larvae eat the feces, and either climb back onto their sloth host as they return to the tree’s base or fly into the canopy in search of another meandering host. In addition, one wild thing about sloths and their feces, is that not only do they use their strong, stubby tail to dig a hole to poop in, but they “dance” as they poop. This is believed to not only be a way to keep the sloth cleaner but also to help spread the feces, and the scent, across a larger area. This is believed to be a tactic to help deter predators from knowing which tree the sloth may be in and is hypothesized to also be a form of territorial marking or other forms of communication between sloths.

Left: A female sloth cleans her newly-born pup. Right: The claws of a young two-fingered sloth.

In short, several adaptations allow sloths to survive in such a unique way, including that they act as mobile, mutualistic ecosystems of their own.

Some other interesting adaptations of sloths are that they have a muscle structure unique to them alone, with fibers that don’t overlap or twist, but stay straight, allowing them to hang for as long as they want and expend nearly no energy whatsoever. Plus, their tendons are similarly designed, creating a combination that allows for extreme strength with minimal energy. In addition, sloths have four-chambered stomachs, like cows, which is odd for small mammals.

Furthermore, sloths are completely colorblind, as in they can’t see any color. This is because they lack cone cells altogether, which are what absorb light to discern colors. This also makes it very hard for them to see in dim light and makes them nearly blind in bright light, or darkness, so, instead, they have an overwhelming sense of smell, which supports the previously mentioned poop-pothesis. In addition, they have special fibrous material that holds their organs in place within their abdomen, allowing them to stay comfortable while upside down. Likewise, they have specialized arteries and veins that keep blood flowing evenly while both upright and upside down, as they can’t rely on gravity as we do.

Furthermore, their hook-like fingers and toes, as seen above, allow them to stay latched onto a branch with no effort, but also allows them, when combined with their unique muscles, to hold on with a grip strength far greater than humans. This means that they can sleep, climb, eat, and even give birth hanging by their claws, as seen above. Yet, it also means that although predators can’t pry them from their perches, they are also found to stay attached to their branches after their death.

From algae making microcracks in hair follicles home to moths that rely on feces, to adaptations that both help and hinder them, sloths are one of Earth’s most unique organisms. Living in Central and South America, these unique mammals need our help.