Gigantism vs Dwarfism: The True Fight of Isolated Evolution

February 7, 2023

From two-foot-long hamsters to three-foot-tall elephants, there are many unique species created by isolation. When isolated, genetic pools can make evolution much more visible than usual, which can lead to the surprisingly common occurrences of insular gigantism and insular dwarfism.

The “spur” of the Italian boot, Gargano, a mountainous peninsula in the Italian province of Foggia, Apulia, was once an island: 12-4 million years ago, during the Late Miocene to Early Pliocene. This period was long enough for dramatic evolution, caused by the isolation of island life.

Insular gigantism is a process in which a species quickly evolves to be larger than its relatives. This most often occurs to prey species, who thrive when facing few predators and abundant resources of isolation. Yet, on Gargano, the growth of prey species also resulted in the growth of predators, although very few in comparison.

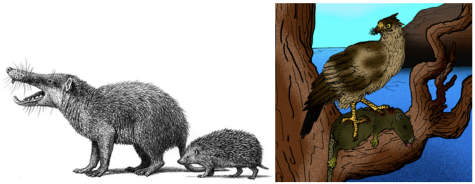

For example, the island was home to Deinogalerix, shown below compared to a modern-day hedgehog. This caused the growth of the genus Garganoaetus, which went from being previously hawk-sized, to the size of a golden eagle while living on Gargano. A rendering of Garganoaetus can also be seen below, holding a species of Mikrotia, another family that experienced rapid evolution and growth.

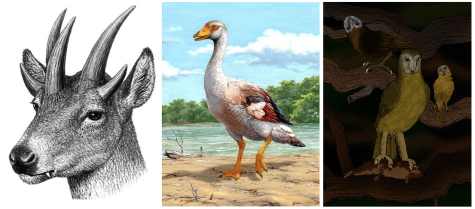

In addition, some other unique species of Gargano include Hoplitomeryx, the five-antlered deer with fangs, Garganormus the flightless goose that is thought to have weighed up to 50 lbs, and Tyto robusta/Tyto gigantea, two species of barn owls that were more than double the size and weight of modern barn owls, pictured below from left to right, respectively.

With these creatures in mind, we have to ask, why does this happen? Insular gigantism, as explained before, most often occurs in prey species, as a lack of predators can call for the reversal of many of the genes that kept them safe. Gargano Island is one of the best examples of insular gigantism in both predator and prey, but insular gigantism can be seen all around the world in a wide variety of species. Again, it is this isolation that allows for such dramatic evolution, as limited gene pools plus prime conditions can lead to rapid change over comparably short periods. This leads to unique adaptations, such as the five antlers of Hoplitomeryx, or the loss of the ability to fly in Garganormus.

The isolation as mentioned above also causes these adaptations to rarely leave their place of origin, making small pockets of unique species, seen nowhere else in the world.

Furthermore, such conditions can also lead to the opposite occurrence, insular dwarfism. This can be seen in some of the most infamous species of Earth’s not-too-distant past, the wooly mammoth.

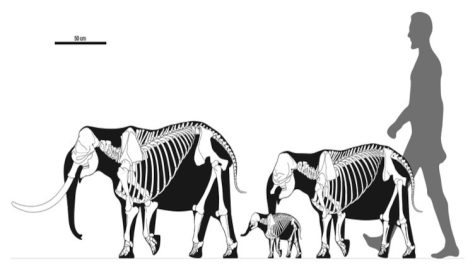

The last mammoths on Earth were a species, Mammuthus primigenius, on the small island of Wrangel, sitting in the Arctic Ocean north of Siberia. This isolation led to insular dwarfism. Insular dwarfism occurs in large species, such as mammoths, elephants, or even horses. Normally, great size can help deter predation, just as being extremely small can; yet, the larger the organism, the more food is required to sustain it. Thus, it is beneficial for a large animal to evolve to be smaller when lacking predators. This is seen most dramatically in the elephants of Malta, Palaeoloxodon falconeri, as seen below, and the mammoths of Wrangel and the Channel Islands of California, two distinct events of the same evolutionary mutation.

Palaeoloxodon falconeri compared to an average human.

Yet, when we consider the fact that it is limited genetic pools that cause such dramatic and short-term change, we also have to consider some of the other impacts of such little diversity. The mammoths on Wrangel Island are one of the best examples of this. It is suspected that at any given point, there were only a couple hundred mammoths on Wrangel, which led to generation after generation of inbreeding. This caused the fourteen-foot tall mammoths of Siberia, with thick wooly coats and a complex social system that relied on scent, to become six-foot tall animals with thin white coats and little to no ability to smell. This loss of smell is suspected to have led to social anarchy. Genetic analysis of their remains also alludes to several other negative mutations.

When a species devolves like this, it is known as a “genetic meltdown.” This occurs when genetic pools become too small, limiting the ability of evolution to remove bad traits from a genome, and causing mutations to spread quickly through a population.

Isolation can lead to truly unique species, from pygmy elephants and mammoths to giant hamsters and hedgehog relatives; insular gigantism and dwarfism are just two of the many astonishing events that can occur in the evolution of Earth’s flora and fauna.