Earth’s First Farmers Weren’t Human

March 6, 2023

When humans first began to domesticate wild plants as crops, around 12,000 years ago, it changed the course of our history forever. Yet, we weren’t the first species on Earth to domesticate wild plants.

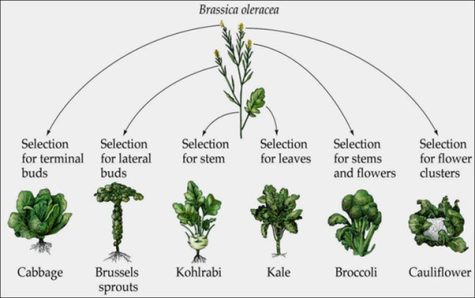

To clarify, domestication is where a species is isolated from its natural environment for so long that it becomes reliant on its domesticator for survival. For example, when humans began to domesticate wild plants, we took wild seeds and planted them in isolated areas, and kept the seeds from those we liked most, planting them in turn. Much like with the animals we raise as livestock and pets, this is known as selective reproduction. This created genetic isolation, as now almost every crop we raise is genetically unique to its wild ancestors. This can be seen dramatically in the selective breeding that occurred to a single wild plant species to create cabbage, kohlrabi, brussels sprouts, kale, broccoli, and cauliflower, as seen below.

The domestication of this one wild plant is an excellent example of selective reproduction.

Likewise, just as we domesticated thousands of species of wild plants, millions of years beforehand, over 30 million years that is, ants began to domesticate fungi. You read that right, ants domesticated fungi, farming them to the point of genetic isolation, creating unique species of fungi that can only be found deep in ant colonies, and can’t survive without the ants that tend them. Yet, the questions have to be asked: how, and why?

The why of this has only recently been discovered, as in 2017 researchers reported that although evidence showed that ants had been farming fungi for over 60 million years, climate change around 30 million years ago might have been the cause for the domestication of the previously externally farmed fungi. When scientists traced the fungi’s genome, it led back to fungi that grew in humid forests across the Americas and the Caribbean, alongside the ancestors of what are now hundreds of species of attine ants. Among these ants is one of the most famous Central American ant species, the leaf-cutters. These ants are renowned for their harvest of foliage above ground, with trains of hundreds of ants carrying cargo far larger than themselves back to their nests. Yet, the ants don’t eat these leaves. Instead, they carry them deep into their colonies and feed the pieces of foliage to masses of carefully tended fungus, as seen below in a controlled environment.

Leaf-cutter ants feeding a fungal farm in an ant farm at the Smithsonian.

The aforementioned climate change caused Earth to cool drastically, lowering the humidity in many regions previously perfect for these ancient ants and their fungi. This likely led the attine ants to bring the fungus they had been farming above ground into their hives. In these large complex colonies, the ants can create prime conditions for their fungus. This allowed the ants to spread beyond the forests, as their food source was now adapted to their lifestyle. Over the next few million years, such isolation created fungus that relies entirely on the ants that feed it, and that can’t reproduce with wild fungus. In addition, this specialization also caused the attine ants to become reliant on their fungus for more than just food, as scientists discovered that the fungus that the ants tend contains a series of nutrients that are vital to the attine ants, which they have stopped producing internally thanks to the surplus found in their crops.

Furthermore, the attine ants have developed such a high level of agriculture that they maintain a single crop without it succumbing to pests, disease, or the various other risks of a distinct lack of genetic diversity. This is achieved through the maintaining of a monoculture of benign and beneficial bacteria alongside their fungal crops, doing so by keeping the hive spotlessly clean, as well as having adapted to secrete a natural antibiotic that acts as a pesticide, killing off parasitic fungus and pests. They have even managed to go as far as controlling pathogens within the hive by keeping pristine environmental conditions within the hive. In short, they maintain entire ecosystems within their colonies to successfully grow their fungal crops.

Leaf-cutter ants tending to their fungal farm.

Leaf-cutter ants tending to their fungal farm.

In comparison, it also has to be taken into account how attine ants such as the infamous leaf-cutters can harvest foliage and create mini ecosystems without harming the ecosystem above ground; especially when it is considered that a colony of attine ants is about the same weight as a cow, and consumes just about the same amount of foliage in the same time period as a cow. With that in mind, how can a colony this large stay in one area without killing everything around it? It has been discovered that their ecosystem has also adapted to them in a variety of ways. For example, some tree species commonly harvested by leaf-cutter ants have been found to begin producing a toxin in their foliage once a certain level of harvest has been reached. It is in such ways that the ecosystem around the ants survives, while still supporting the colony that maintains the soil of said ecosystem.

From agricultural advancement far beyond ours, to specially adapted crops and farmers that coexist in a nearly unimaginable balance, the first true farmers of Earth were the attine ants of Central America.